On June 16, 2014, the American Freedom Law Center (AFLC) filed its opening brief in the United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit, requesting that the federal appeals court reverse two lower court decisions that permitted the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) to censor the display of pro-Israel / anti-jihad advertisements on its public buses. The MBTA rejected the advertisements, claiming that they demeaned and disparaged Muslims.

AFLC filed the two lawsuits in the U.S. District Court for the District of Massachusetts on behalf of the advertisements’ sponsors, the American Freedom Defense Initiative (AFDI), a pro-Israel advocacy group, and its executive directors, Pamela Geller and Robert Spencer. The lawsuits challenge the MBTA’s speech restrictions under the First and Fourteenth Amendments. In each case, AFLC filed a motion for a preliminary injunction, requesting that the court immediately order the MBTA to display the advertisements. The district court denied the motions, ruling that in light of a prior controlling decision from the First Circuit, the MBTA’s rejection of the advertisements was “reasonable.” Seeking to test the First Circuit’s precedent, AFLC immediately appealed both rulings, and the First Circuit consolidated the two cases.

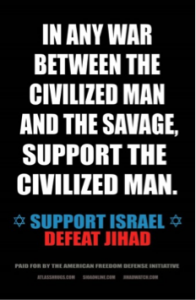

The dispute began in October 2013, when the MBTA accepted for display a controversial pro-Palestine / anti-Israel advertisement. In direct response, AFDI submitted an ad that stated: “In any war between the civilized man and the savage, support the civilized man. Support Israel. Defeat jihad.”

The MBTA rejected AFDI’s advertisement because it inferred that the use of the noun “savage” demeaned all Muslims and Palestinians because “war” might not be violent war and “jihad” might refer to a Muslim’s duty of introspection and self-improvement rather than violent acts of terrorism. In its ruling denying AFLC’s request for an injunction, the court agreed that the MBTA’s view of the ad was not “the most reasonable,” stating:

[T]he Court agrees with the plaintiffs that the most reasonable interpretation of their advertisement is that they oppose acts of Islamic terrorism directed at Israel. Thus, if the question before this Court were whether the MBTA adopted the best interpretation of an ambiguous advertisement, it would side with the plaintiffs. But restrictions on speech in a non-public forum need only be reasonable and need not be the most reasonable. . . . In this case, the Court understands the inquiry to require only that the MBTA reasonably interpret the ambivalent advertisement. In light of the several divergent interpretations, it was plausible for the defendants to conclude that the AFDI Pro-Israel Advertisement demeans or disparages Muslims or Palestinians.

AFLC filed an immediate appeal of this ruling to the First Circuit.

Following a careful review of the district court’s decision, AFDI submitted a revised ad that replaced “savage” with “those engaged in savage acts” and “jihad” with “violent jihad.” The MBTA accepted this advertisement.

As a result and to further test the “reasonableness” of the MBTA’s advertising guidelines, AFDI submitted a third advertisement, this time replacing “those engaged in savage acts” with “savage,” but clarifying the word “jihad” to include only “violent jihad,” thereby removing any ambiguities.

Surprisingly, the MBTA rejected this advertisement despite the “violent jihad” clarification (i.e., the “jihad” in the ad refers to savage acts of terrorism), claiming that the advertisement was, once again, demeaning and disparaging to all Muslims. This decision prompted AFLC to file a second federal lawsuit. And despite its prior ruling, the district court denied AFLC’s request for an injunction, prompting an immediate appeal of that ruling.

As stated in AFLC’s opening brief filed today with the First Circuit:

[T]he MBTA’s only proffered justification for restricting Plaintiffs’ speech under its advertising guidelines is that the rejected advertisements “contain[] material that demeans or disparages an individual or group of individuals.” However, . . . the application of this guideline here was a subjective endeavor that was inherently viewpoint based and entirely unreasonable.

Indeed, the fact that “jihad” might also have a non-violent meaning does not render the public stupid. Thus, it is clear to any reasonable person that the use of the term “jihad” in the context of the “war” being waged in Israel does not disparage those Muslims (Palestinian or otherwise) engaging in a self-reflective internal struggle. And to further illustrate this point, federal court opinions in cases prosecuting terrorism (i.e., savage acts) routinely utilize the term “jihad” to mean terrorism without disparagement because the use of the term to describe terrorists fighting in the name of Islam and committing terrorist acts in the name of Islam is ubiquitous, and the meaning of the term is again clear to any reasonable person (and, in particular, to the MBTA’s ridership who just recently experienced a savage act of jihad at the Boson Marathon in 2013).

AFLC Senior Counsel David Yerushalmi commented:

“The MBTA cannot escape the conclusion that its censorship of our clients’ ads was a subjective endeavor that was viewpoint based and entirely unreasonable. Indeed, the bedrock principle of viewpoint neutrality demands that the government not suppress speech where the real rationale for the restriction is disagreement with the underlying ideology or perspective that the speech expresses.”

AFLC Senior Counsel Robert Muise commented:

“The Supreme Court has long held that viewpoint discrimination is prohibited in all forums. Indeed, the First Amendment forbids the government to regulate speech in ways that favor some viewpoints or ideas at the expense of others. When the government targets particular views taken by speakers on a subject, it is a blatant violation of the First Amendment.

“In this case, the MBTA has willingly accepted controversial advertisements that discuss the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Consequently, the MBTA is not restricting the subject of our clients’ ads, but their views on the subject. This is a classic form of viewpoint discrimination that is prohibited by the First Amendment.”